There's hope for American furniture.

Posted Thursday, June 18, 1998, at 3:30 AM ET

Goldberger, while rejoicing that sophisticated design has finally reached the American masses, rightly lamented that it has come at the price of individual variation and taste. Just as the Gap look has become as much of a uniform now as the preppy aesthetic it replaced, so also has the Pottery Barn look standardized our homes as vacuously as any traditional style. But in the big picture, the Gapping of American furniture has actually been one of the most welcome developments in recent years. It has made good design easily accessible and, paradoxically, opened opportunities for American manufacturing that may help consumers develop a sense of personal style.

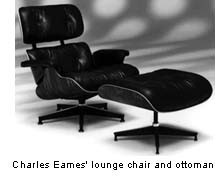

Americans  have always had bad taste in furniture. It's been hard to say, though, whether we're innately philistine in our artistic judgments or have merely been deprived of decent choices. Until the 1930s, most furniture that was well designed came from Europe, was priced accordingly, and was off-limits to most consumers. Then things started to change, slowly. The Bauhaus design school introduced the idea that good design could be had by anyone; in the 1950s the Bauhaus aesthetic led to the American manufacture of such modernist (but still too pricey) classics as Charles Eames' lounge chair and ottoman and Arne Jacobsen's Egg Chair. In the '60s, an Englishman named Terence Conran opened a store in London called Habitat, selling what has come to be called "transitional" furniture--mixable pieces so neutral and inoffensive they could fit into any environment. Conran brought the idea to the United States in 1977, opening his chain. Still, big manufacturers such as Ethan Allen, Broyhill, and Drexel continued to dominate the market with safe, conservative styles or traditional looks from the last century.

have always had bad taste in furniture. It's been hard to say, though, whether we're innately philistine in our artistic judgments or have merely been deprived of decent choices. Until the 1930s, most furniture that was well designed came from Europe, was priced accordingly, and was off-limits to most consumers. Then things started to change, slowly. The Bauhaus design school introduced the idea that good design could be had by anyone; in the 1950s the Bauhaus aesthetic led to the American manufacture of such modernist (but still too pricey) classics as Charles Eames' lounge chair and ottoman and Arne Jacobsen's Egg Chair. In the '60s, an Englishman named Terence Conran opened a store in London called Habitat, selling what has come to be called "transitional" furniture--mixable pieces so neutral and inoffensive they could fit into any environment. Conran brought the idea to the United States in 1977, opening his chain. Still, big manufacturers such as Ethan Allen, Broyhill, and Drexel continued to dominate the market with safe, conservative styles or traditional looks from the last century.

Pottery Barn and the others have turned Americans on to furniture. According to Barnard's Retail Trend Report, since mid-1996, consumers have been spending more on the home than on apparel ($296.3 billion vs. $277.9 billion in 1997). This sudden interest can also be attributed to other causes--we're older and nesting; we're spending more time at home; we're making bolder purchases because of a better economy. But what's noteworthy is that it's young people who have developed a taste for cool places to sit and sleep. A survey by the Home Furnishings Council found that consumers under 35 were most likely to agree with the statement "I like to shop for furniture." Young buyers are growing up with good design around them--in clothes, in advertisements, in movie sets--and this improved climate surely makes them more discriminating shoppers.

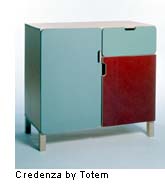

Paradoxically, the Gapping of furniture has made it easier for new, innovative design companies to thrive. You could see the stirrings of a creative revolution at this year's International Contemporary Furniture Fair, held a few weeks ago in Manhattan. The fair still showcased some of the arts-and-craftsy "novelty" elements (lights in the shape of pigs or brassieres, chairs made from shopping carts or traffic barricades) that earned it the "bad flea market" label when it began a decade ago. But there were also a dozen small designer-manufacturers producing funky yet rational design at affordable prices. Even though these items cost a bit more than Pottery Barn fare, they were no doubt affected by the success of that store's clean, simple lines. Blu Dot Design, for instance, offered its handsome and functional Uptown series: a cocktail table ($499), sideboard ($899), and media cabinet ($649) of cherry, chrome, and sandblasted glass that discreetly allow for both storage and display. Although the Minneapolis-based company is just a year old, its three twentysomething founders have already got orders from more than 100 retailers around the country. They've been written up in Newsweek, the New York Times, and an array of design magazines. Most telling of all, the series' cocktail table and sideboard are now part of Chandler and Joey's living room on Friends.

In addition, medium-size companies such as Directions are now offering sophisticated design and manufacturing quality at department-store prices, retaining an attention to fine detail that the mass chains lack. Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and Donna Karan have also got in on the act, introducing their high-quality (though far from original) "home collections." Lauren has already covered a quarter of Bloomingdale's furniture department with haute preppy ensembles of paisley, tartan plaid, and corduroy. The rise of "boomer casual" has even forced the major manufacturers to move beyond their perennial colonial reproductions. Their more "modernized" furniture looks as if it were designed by a committee tallying up market research, but it's a start.